Amyr Klink’s 100 Days between Sea and Sky

By Rob Packer

The story of the first man to row solo across the South Atlantic from Namibia to Brazil isn’t typical reading material for me (this is despite my own rowing past, and vaguely knowing half of a duo who rowed across the North Atlantic and a former secondary-school teacher and his wife who are about to). In other words, I expected Brazilian explorer Amyr Klink’s account of his 1984 journey, Cem dias entre céu e mar—100 Days between Sea and Sky and out of print in English—to be mildly interesting at best. I was wrong: the book is surprisingly fascinating and has made me curious about the sailing expeditions he has done.

Of course, the journey is the focus but what makes the book special are the meditations on Klink’s motivations and meticulous preparations. Sometimes the expedition seems nothing more than the culmination of childhood curiosity developed exploring the mountains and islands around Paraty, a colonial town on the coast between Rio and São Paulo; one of the book’s most memorable sections tells the story of a 12-year-old Amyr going hiking with a friend and coming across a previously unknown quilombo (a village originally of escaped slaves that still exist in parts of Brazil).

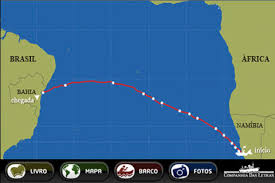

This curiosity mixes with a strong influence from the maritime themes that permeate Portuguese literature: for example, while describing the currents that determined his route, Klink quotes Fernando Pessoa, the greatest modern Portuguese poet, and then goes on to say that his route is fundamentally the one followed by Portugal’s 15th-century navigators and mentioned in Camões’ Lusiads, the seminal work of Portuguese literature. After all, the currents used by Vasco de Gama, Diogo Cão, Pedro Álvares Cabral and other Portuguese navigators haven’t changed.

Reading the book in the GPS age, though, parts of the book seem like a historical artefact as the on-board navigation tools amount to sextants, chronometers, astronomical calculators and trigonometry; and if it was cloudy at midday, then he couldn’t be sure of where he was. His encounters with dolphins, a crèche of whales, dorados and sharks would likely be much the same today, although who knows for how much longer given the state of the world’s oceans.

Surprisingly, there are no photos—Klink’s camera stays in Namibia after an accident—and the book clocks in at 150 pages. Rather than falling into the trap of a diary format, the chapters are chronologically structured around events and Klink’s own elastic notion of time that was either “so exact as to feel every tenth of a second of every hour or so vague that centuries would mean nothing”. And ultimately, conciseness and a lack of photos allow Klink’s strengths as a storyteller to come to the fore.