What does it mean to be Lebanese in America?

This post is written by Amanda Eads, a Sociolinguistics student at NC State University. It is Part 1 of 3 in a series that describes the survey she conducted and her analysis. If you are of Lebanese heritage and would like to participate in this study you can find the questionnaire here: http://goo.gl/forms/KLnFfQbmzv

I’ve had the opportunity to ask this question several times over the past year while conducting interviews and surveys among the Lebanese community in North Carolina.

Some say being Lebanese in America means having pride in both countries, blending the best of both cultures, being a cultural ambassador and breaking down preconceived notions. Others say it means being an entrepreneur, making the best use of opportunities offered in the US. Still others say that it is the best gift God ever gave! While the responses I’ve received have been remarkably informative and interesting (and even amusing) one thing is clear: everyone has their own unique answer informed by their own unique story.

Participants of Questionnaire

This past academic year I devoted my time to sociolinguistic research in this community. The bulk of my research has concentrated on Lebanese immigrant identity and language practices. As a sociolinguist, my goal is to examine linguistic variation within the community. In order to do so, I required a greater understanding of how the Lebanese see themselves. In attempting to develop such an intimate knowledge, I conducted interviews and used an online questionnaire. So far, I have collected a total of 47 responses to the questionnaire.

- Participants consisted of 24 males and 23 females.

- 45 out of 47 have obtained an Associates degree or higher.

- The 2 participants who do not report higher education are still attending or recently graduated from high school.

- 7 participants were born between 1930-1950

- 33 were born between 1951-1985

- 7 were born between 1985-2000.

On the questionnaire the participants were provided several options for identifying their nationality. Here are the totals for each nationality:

- 4 American

- 1 American-Arab

- 9 American-Lebanese

- 10 Lebanese

- 22 Lebanese-American

- 1 Lebanese-Dutch

How identity is defined

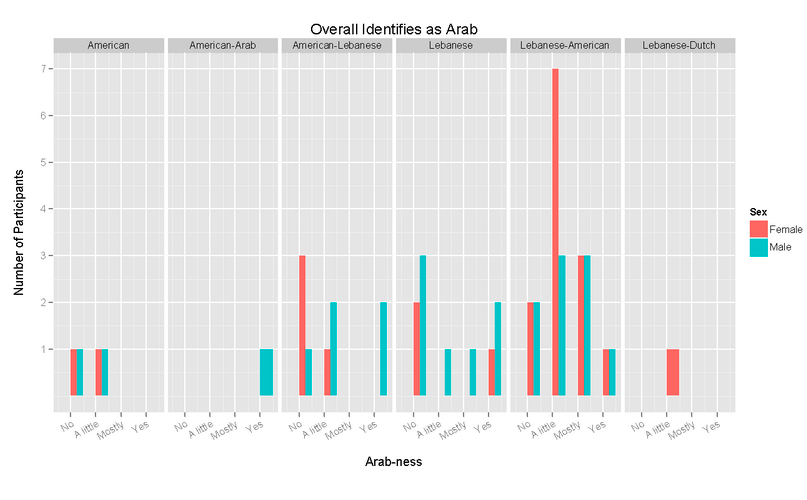

The following graphs show how the participants’ nationality and their overall identification as Lebanese, Arab, and American impact identity.

Analysis of Data

The graphs reveals the mélange that is Lebanese identity. Bucholtz and Hall (2003:371) claim that “obscuring differences within a common identity” is often necessary in order to greater distance ‘Others.’ These participants are all Lebanese. They or their ancestors have migrated to the United States from the region that today we know as Lebanon. Historically (1880 – 1940s), they were known as “Syrians,” and they regarded themselves as such in public and private. More recent immigrants (1960s and thereafter) began to refer to themselves as Lebanese-Americans. Yet when looking further into how the Lebanese view themselves and their own identity it becomes clear the earlier appellation and identity has been obscured in order to attain uniformity, greater strength and recognition for the overall Lebanese community here in the States.

Arab Identity and Lebanese as Arab

While each of the participants have their own unique identity, I still found few trends during my analysis that I will discuss below and in the two following blogs. On the questionnaire the participants were asked if they believed the Lebanese are Arab; 36 of the participants answered yes while 11 individuals claimed no the Lebanese are not Arab. The most significant result I found in my analysis shows a correlation between having a strong Arab identity and believing Lebanese are Arab.

Figure 1: The figure above shows the number of participants and how they identify with Lebanese culture. The histogram is faceted by the participant’s identified Nationality and colored for sex.

However after further examining the data, only 15 participants responded with “Yes” or “Mostly” for overall identifying as Arab despite 36 participants believing the Lebanese are Arab. Clearly, there is a group of participants that believe the Lebanese are Arab but do not personally identify as Arab. The participant who identified as American-Arab shows strong Arab identity while those identifying as American and American-Lebanese reveal a weak Arab identity. There is more variety in the answers from those identifying as Lebanese and Lebanese-American although the trend is also toward a weaker Arab identity. As an interesting side note, the questionnaire gave the nationality option of Arab-American but this was not chosen by any of the 47 participants.

Lebanese Identity and American Identity

The second most significant result in my study revealed that being Lebanese-American seems to correlate with having both a strong Lebanese and strong American identity.

Figure 2: The figure above shows the number of participants and how they identify with American culture. The histogram if faceted for the participant’s identified nationality and colored for sex.

Individually the graphs show that those who identify as American-Arab, Lebanese and Lebanese-American report the strongest Lebanese identity while those who identify as American or American-Lebanese trend towards a weaker Lebanese identity. On the other hand, those who identify as American, American-Arab, American-Lebanese and Lebanese-American show the strongest American identity while the Lebanese and Lebanese-Dutch trend towards weaker American identity. As such, with the exception of the American-Arab, the trends reveal that overall Lebanese-American is the nationality that claims both strong Lebanese and strong American identity. While this is a generalization, it is interesting to explore the differences between the nationalities and the rankings within the hyphenated identities. This exploration will continue In the following two blogs.

Figure 3: The figure above shows the number of participants and how they identify with Arab culture. The histogram is faceted for the participant’s identified nationality and colored for sex3.

Figure 3: The figure above shows the number of participants and how they identify with Arab culture. The histogram is faceted for the participant’s identified nationality and colored for sex3.

Identity in the homeland is often very different from identity in a migrant’s host society. While migrants bring their ‘home’ identity with them to a new place, they often face unexpected challenges and adjustments. These challenges often come in cultural and linguistic form. As evidenced by this study among countless others, immigrants often overcome and adapt to these challenges by claiming a hyphenated identity. Frances Giampapa (2001) defined hyphenated identity as the negotiation of the old and new; or the negotiation of where they have been and where they are now. Thus, the hyphenated individuals in this study are negotiating their Lebanese heritage and their newfound American-ness. The participants in this study show that this negotiation can manifest itself in many forms. So what does being Lebanese in American mean? Well, it can mean many things but being Lebanese-American means having both a strong Lebanese and strong American identity.

If you are of Lebanese heritage and would like to participate in this study you can find the questionnaire here: http://goo.gl/forms/KLnFfQbmzv

Courtesy Moise A. Khayrallah Center for Lebanese Diaspora Studies