Half man, half insect

James Lasdun is impressed by a novel of wretchedness and exile in Montreal.

De Niro’s Game, the riveting Impac-winning debut novel by the Lebanese-born writer Rawi Hage, ended with its young hero, recently escaped from wartorn Beirut, wandering around Paris in a delirium of memories from his blood-spattered past and feverish stratagems to consolidate his precarious present. Cockroach, Hage’s more capacious, ambitious second novel, takes exile as its point of departure, and reads almost as a sequel to the first.

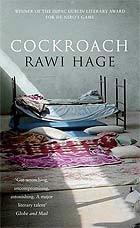

- Cockroach

- by Rawi Hage

- Find this on the Guardian bookshop

Montreal replaces Paris as the city of refuge, but the unnamed hero is substantially the same figure: a small-time crook, haunted by similar memories, enmeshed in a similar world of émigré hustlers and desperadoes, afflicted by similarly elemental problems of survival, and unfolding his noirish tale of desire, vengeance and redemption in the same strikingly idiosyncratic style, at once hard-boiled and hallucinatory, like that of some hoodlum-visionary freshly disembarked from Rimbaud’s Drunken Boat.

The style is what you notice first in both books, its salient feature being a kind of compulsive efflorescence of imagery at everything the narrator’s mind settles on. Where your average British or American writer would opt for a single, precise image to illuminate an object or idea, Hage (who writes in English) likes to throw in all the alternates and variants he can think of, good and bad alike, as if he’s constitutionally unable to forgo any possibility of deepened or extended resonance. A lover’s urine going down the drain makes him think of a kite string, an umbilical cord, of salvation and rebirth, of “golden threads of celebration everywhere”, and then some. Men jerking off at a porno in Beirut form a compound hieroglyph of work, war, shame, lust and marriage as associations pile up in a recollected glimpse; they stood with “their shoulders tilted forward like the silhouettes of fishermen against crooked horizons scooping fish by the light of a sinking sun, and they blasted their handkerchiefs with the bangs of expelled bullets, wounding their pride and finally holding up images of past lovers and their own unsatisfied wives”.

The risks of overkill in this kind of writing are obvious, but what would quickly pall in most other writers remains curiously invigorating in Hage. Partly it’s that there’s something winningly hit and miss about the images themselves – an emphasis on wild energy rather than laboured precision – and partly it’s an underlying sense that these extravagant descriptive arabesques (the word seems unavoidable) are in fact the reverberations of some seismic disturbance experienced by their speaker; little verbal aftershocks testifying to an authentic crisis.

Crisis is certainly the defining condition for the narrator of Cockroach. When we first meet him he’s under court-ordered supervision by a therapist, having just tried to hang himself. He’s also penniless, loveless and extremely hungry. The first part of the novel consists of excursions into the icy city to remedy this state of affairs: scrounging, thieving, chasing a small debt, trying to win over an Iranian girl he has fallen for, and so on, alternating with his visits to the therapist. The latter functions partly as a device to enable the controlled release of information about a past trauma concerning his role in his sister’s death, and partly – more interestingly – to analyse and amplify the book’s governing idea, which is the narrator’s abiding fantasy that he is half cockroach.

Just as the world of action movies formed an imaginative mirror for the events in De Niro’s Game, so this insect fantasy lends Cockroach its own dimension of sustained, transfiguring metaphor. Kafka obviously comes to mind here, but the handling of the idea, often dazzling in its own way, is notably un-Kafkaesque. Where Kafka writes Gregor Samsa’s metamorphosis as a passion play of Christ-like suffering and forbearance, Hage works the subject for something much more caustic and defiant. Insecthood, for his victim, is a phantasmal extension of his own multifaceted idea of himself: as immigrant outcast, seething sensualist, Dostoevskian Underground Man, undetectable thief, future inheritor of the earth, agent of exposure among the hypocritical bourgeoisie and all-round connoisseur of the tang and sting of reality.

“I will show you who I really am,” he says to his sympathetic therapist (whose home he breaks into for no very good reason, other than to spook her). “And it is not pretty.” Revelling in himself rather than self-reviling (the suicide attempt never feels quite serious), he descends more from Céline, Genet and Burroughs than from Kafka. But there’s also, I think, something uniquely contemporary about him, namely the peculiar, unlovely knowingness of today’s professional underdog, who understands a little too well how to exploit his own victim status, particularly with women.

To a fellow impoverished immigrant, for instance, he recommends playing “the fuckable, exotic, dangerous foreigner”. The cynicism of this, while entirely convincing, undermines his frequent rants against the sleek businessmen and women of his adoptive city. Basically, he’s them without money, which in turn makes his tirades sound less and less like genuine moral critique, and more like whingeing or attitudinising. About halfway through, this becomes mildly problematic.

Only mildly, because Hage seems uneasily aware of it himself. At one point he supplies a fully hallucinated giant albino cockroach to confront his narrator with certain unpalatable truths: “in your deep arrogance you believe that you belong to something better and higher …” This side of the dialectic might have been usefully developed a little further. But after all this is a novel, not a tract, and Hage ultimately resolves the matter (or at least distracts the reader from it) in a conventionally novelistic manner: by thickening the plot.

His narrator gets a job as bus-boy in an Iranian restaurant, and meanwhile becomes more deeply involved with Shohreh, his troubled Iranian lover, herself a poignant study in a certain kind of traumatised sexuality. Like him, she is haunted by an episode from the past, similarly shrouded in pain and shame. As the reciprocal truths slowly emerge, a sinister Iranian fat-cat begins dining regularly at the restaurant with his bodyguard. It turns out that he and Shohreh have met before, under considerably darker circumstances. And suddenly the narrator has a chance to redeem himself from his own past cowardice.

Most fiction writers are primarily either stylists or plotters, but Hage is clearly both. There’s a slight jolting sensation as the narrative shifts gear from poetic to cinematic, with guns and knives and elaborately contrived set-ups replacing the earlier evocations of drains and flesh and wintry streets, but it’s all managed with great brio and expertise, and it all comes to a very satisfying climax. And if, a little later, you find yourself feeling that the book has after all raised more questions about the condition of wretchedness than its ending quite resolves, this is only further evidence of Hage’s large and unsettling talent.

• James Lasdun’s It’s Beginning to Hurt is published by Jonathan Cape