‘It’s Impossible To Forget’: Descendants Of Armenian Genocide Want Legacy Of Those Killed To Live On

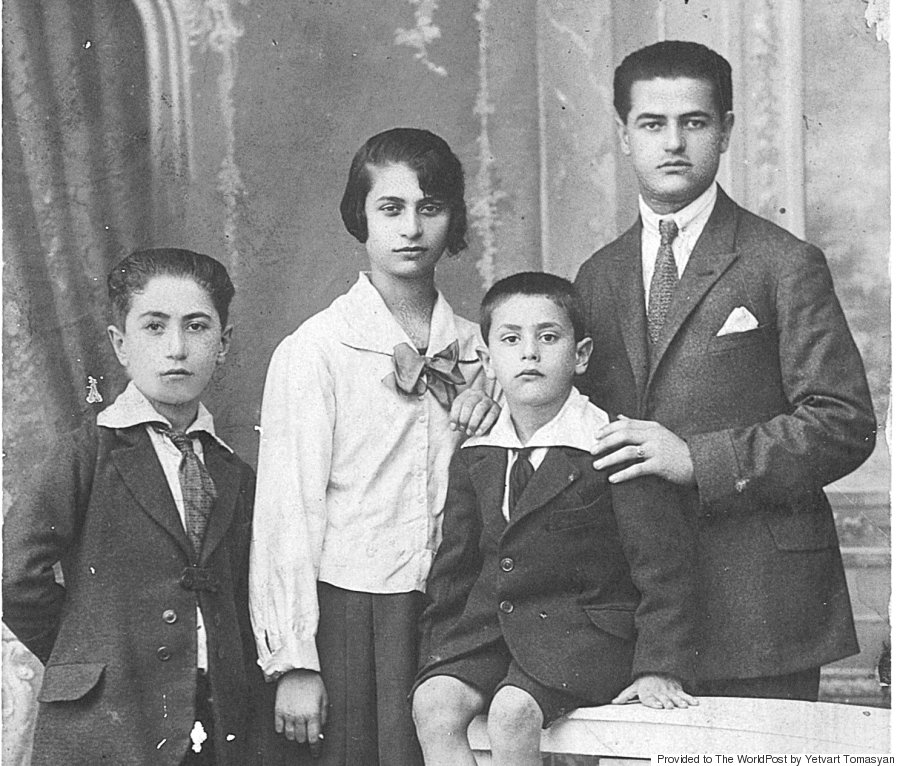

Yetvart Tomasyan’s father, Bedros (second from right), poses with his family for a photograph in the early 1900s in the Ottoman Empire, now modern-day Turkey. The family photo is missing a small boy, Bedros’ brother, who descendants say died in a death march to northern Syria with his grandfather.

ISTANBUL — Mari Tomasyan was born into a family of ghosts. In 1915, just a few years before she was born, Ottoman Turks forced 35 of her relatives on a death march toward the Syrian Desert. Only a few survived.

Now, at 95, she clings to the past with a quiet strength. As almost a century of memories begin to fade with age, she hands down the past to her own children and grandchildren.

“These scary things, they disappeared over time,” she said in her family home in Istanbul, recalling the intense fear that consumed her childhood. “But the genocide is not forgotten. It’s impossible to forget.”

Tomasyan’s relatives were just a handful of an estimated 1.5 million Christian Armenians killed between 1915 and 1917, according to Armenians,news reports from the time and historians.

Armenians killed by Ottoman Turks during the Armenian Genocide in 1915.

The descendants of survivors tell a collective horror story: Families torn apart, seemingly endless death marches, starvation and rampant disease, humiliating gang rape, mass graves filled with the bloated bodies of men, women and children.

Despite Turkey’s impassioned insistence that there was no genocide, instead labeling the Armenians as casualties of warfare and traitors who tried to bring down the Ottoman Empire, Armenians are making sure the legacy of those killed lives on. With only a small number of genocide survivors still alive, their kin are passing on the history in hopes that such a massacre will never happen again.

Tomasyan’s 65-year-old son, Yetvart, has devoted his life’s work to the Armenian cause. It’s why he founded Aras Publishing House 22 years ago, publishing solely Armenian literature in both Armenian and Turkish.

Yetvart Tomasyan and his 95-year-old mother, Mari, sit in their family home in Istanbul.

“Armenians in this country were described as worse than worms,” he remembered, thinking back to when he was younger. “What could we do? We had to express ourselves. The only weapons we have are our books, literature, culture and art.”

The Armenian genocide remains one of the most sensitive issues in Turkey, a hundred years on. When Pope Francis called attention earlier this month to the mass killing, labeling it a genocide, Turkish Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu accused the religious leader of prejudice and Ankara recalled its ambassador from the Vatican.

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, despite making a noteworthy conciliatory statement last year, dismissed any accusations of genocide last week.

“It is out of the question for there to be a stain, a shadow called ‘genocide,’ on Turkey,” he said.

State-provided textbooks and government statements still often paint Armenians in a negative light, saying that many Christian Armenians who were deported or killed had taken up arms in support of Russia in its quest to seize Eastern Anatolia (now part of modern-day Turkey) during World War I.

Turkish officials have offered their condolences to the descendants of Armenians killed in 1915, but the state maintains that the Armenians were killed as a result of unrest that gripped the Ottoman Empire, not systemic ethnically motivated slaughter.

This year, many Armenians hoped President Barack Obama would commemorate the anniversary by calling the mass killings a genocide — a politically loaded term the U.S. government has danced around for years. But this week, the White House said it would still not use the “g” word, citing “regional priorities.”

This is the scene in Turkey in 1915 when Armenians were marched long distances. Hundreds of thousands of people were said to have been massacred. Others starved to death or died of disease along the way.

For Yetvart Tomasyan, April 24 — the same day a century ago that authorities arrested 250 of Constantinople‘s best and brightest intellectuals in the first wave of deportations — is an opportunity for the country to move forward and make real progress. But he fears it may be awhile before Turkey truly atones for its past.

“Human beings tend to forgive and forget. That’s what is normal,” he explained as his mother closed her eyes, sunlight pouring through the windows and onto her face. “For a hundred years, even though we suffered, we tried to live our lives. But we are living with blood on this land.

His country’s genocide denial has only encouraged the aging intellectual to learn his own family heritage inside and out. He’s spent decades tracking down long-lost relatives in honor of his father, a genocide survivor, who until the day he died in 1975 searched for his brother long after he was hauled off on a death march when they were boys.

“For a hundred years, even though we suffered, we tried to live our lives. But we are living with blood on this land.”

While Yetvart Tomasyan takes great solace in knowing his past, many Armenians in Turkey grow up with only tidbits of their own history — pieces of a puzzle that, as the years go by, become more difficult to put together.

“I am looking for my kin,” one recent advertisement read in the Istanbul-based Armenian weekly newspaper Agos, where people frequently publish messages searching for descendants of relatives separated during the chaos and bloodshed of 1915.

The message goes on to describe a bridge in the foothills of Mount Tendürek, a volcano in eastern Turkey close to the Iranian border, named after a large family who lived there before being forced from their homes in a village once known as Nonpariz.

“The only person left behind in Nonpariz village was the 20 year-old little sister of [Grandfather] Ayvaz called Agcig who married a Kurdish landlord, Kamil.”

According to the person who posted the message, Agcig was only allowed to stay because she converted to Islam and changed her name to Güli.

“Today, one of the Güli’s (Agcig’s) grandchildren is looking for surviving relatives descended from his or her great-grandfather,” the message read.

It’s just one message of many, according to Pakrat Estukyan, an editor at Agos. The newspaper frequently receives phone calls and emails from Armenians — mainly young people — who are trying to connect the dots of their lineage.

“They’re looking for their roots,” he explained in a sunny courtyard at the Agos office in Istanbul. “They’re trying to reach out.”

Estukyan says that despite Turkey’s century-long denial of the Armenian genocide, things have gotten better for Armenians in recent years. With the shocking assassination of Hrant Dink, a leading Turkish-Armenian journalist and former Agos editor-in-chief, by a Turkish nationalist in 2007, came mass outcry. Estukyan says Dink’s murder paved the way for a more open space where Armenians could explore their identity.

“At least people can now say they’re Armenian,” he said. “[The word Armenian] used to be used an insult openly in Turkey.”

While many Armenians have come to embrace their heritage, despite fear of backlash, Estukyan says there is still a long road ahead for the minority group.

Countless numbers of people are still hiding their heritage. Others are raised as Muslim Turks and, later in life, discover they are Armenian.

Many orphans were taken in by Turkish families after the genocide and raised as their own. Other Armenians converted to Islam and changed their names in an effort to save their own lives.

As the descendant of genocide survivors, 55-year-old Sadik Bakircioglu says he will never forget the day his father sat him down — then just a young schoolboy — and explained why the other children called him a kafir, or infidel, despite the family praying regularly at the local mosque.

“We are not kafirs,” he remembered his father saying. “We believe in something. We are Armenian. We are Christian.”

But his parents kept their identity a secret, haunted by grisly killings that took the lives of much of their family.

One story, in particular, stuck with Bakircioglu, as told by his parents: His grandfather, weakened by the excruciating death march, told the Ottoman Turkish guards they would just have to drown him instead of forcing him onward toward the Syrian Desert. Many of his children had already been killed, and he knew he couldn’t survive the impossible journey. And so, as the story goes, they held him underwater until he died.

Bakircioglu’s parents went to their graves as Muslims, terrified of what misfortune might come to the family if they revealed their true identities. But he has chosen a different path, living openly as an Armenian and attending an Armenian church in Istanbul.

“I was angry that he didn’t speak up,” he said, speaking of his late father and his family’s lifelong secret. “Why didn’t you stick together?”

It’s this same fear that Yetvart Tomasyan, the book publisher, hopes will dissipate with future generations.

Turkey may not recognize the genocide anytime soon, but he hopes Armenians in Turkey will find strength in their past in the meantime.

“This is what I’ll tell my grandchildren: We’re here after 100 years,” he said, smiling, with his mother by his side. “They couldn’t annihilate us. We are here like a green tree, giving fruit.”

Yetvart Tomasyan’s father, Bedros, poses for a photograph in the early 1900s.

Burak Sayin contributed reporting from Istanbul.

</hh–photo–armenia-death-march–2849016–hh></hh–photo–armenian-genocide–2849030–hh>