The Gypsies of Lebanon:

by Dr. G. A. Williams

Cultural and religious pluralism contribute to the mystery and richness of Lebanon. At times this pluralism is explosive. For 15 years, from 1975 to 1990, Lebanon was plunged into a civil war that violently divided the country into regions controlled by religious and ethnic factions, including Sunni, Shiite and Druse Muslims and Maronite Christians. The diverse interests of the Lebanese, Palestinians, Israelis and Syrians fueled the war even as they each constitute an ingredient to the country’s make-up. Seventeen religious communities inform the people’s religious consciousness. Social discontinuity is also a major factor in Lebanon’s pluralism pitching the poor (Christians and Muslims) against the rich (Christians and Muslims). On the fringes of this diverse, even fragmented social order stand the Dom (Gypsy) communities.

Although the Dom of the Middle East and North Africa have a common ancestry they are not a homogenous group. The communities in Lebanon display varying outlooks on life as well as variance in language and living conditions.

Dom are found in small pockets throughout Lebanon yielding a conservative estimate of 8,000 people. Dom families typically have seven or eight children. One man near Beirut spoke proudly of his 24 children all of whom were born to one woman. Several clusters of Dom can be found in and around Beirut, Jubayl, Tripoli and the Bekaa Valley. Many more single-family units are scattered throughout the country.

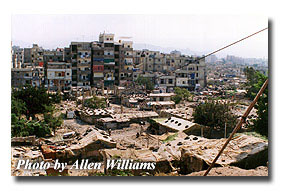

The region of modern Lebanon and Syria is historically a center point or cross roads for migration. Even today Gypsies can be found moving back and forth from eastern countries such as Iran, Iraq and Saudi Arabia. One interviewee spoke of the modern day, nomadic Gypsies who still travel these “trade routes” with no regard for national borders. In the Bekaa Valley they live in tents and in the huts of migrant workers, but in Beirut they live in shantytowns. The shantytowns have grown up in areas that were devastated during the recent war. Water, sewage and electricity are not generally available; thus the unsanitary conditions breed their own problems. The Lebanese government has scheduled the shantytowns for reconstruction. When the reconstruction begins the Dom will be displaced./1 Within the shantytowns the Dom live in close proximity to other ethnic groups (such as Palestinian refugees and poor Lebanese) yet they maintain their own closely guarded identity. The casual observer may not realize this since they identify themselves to strangers as Bedouin, Turkmen, Syrian or Lebanese when possible preferring to keep their actual identity a secret. Around Beirut the Dom like to be known as Turkmen or Bedouin primarily as an alternative to being known by the derogatory Arabic term “Nawar.”

In the Bekaa Valley they live in tents and in the huts of migrant workers, but in Beirut they live in shantytowns. The shantytowns have grown up in areas that were devastated during the recent war. Water, sewage and electricity are not generally available; thus the unsanitary conditions breed their own problems. The Lebanese government has scheduled the shantytowns for reconstruction. When the reconstruction begins the Dom will be displaced./1 Within the shantytowns the Dom live in close proximity to other ethnic groups (such as Palestinian refugees and poor Lebanese) yet they maintain their own closely guarded identity. The casual observer may not realize this since they identify themselves to strangers as Bedouin, Turkmen, Syrian or Lebanese when possible preferring to keep their actual identity a secret. Around Beirut the Dom like to be known as Turkmen or Bedouin primarily as an alternative to being known by the derogatory Arabic term “Nawar.”

Few Dom in the cities have steady jobs. They can be seen begging in the streets; playing drums, flutes or other instruments at weddings and parties; fortune telling; as well as working as day laborers. Dom children sell candy, nuts, gum, etc. in the streets rather than attending school. One Lebanese reported that in the past the government placed a band on Gypsies to keep them out of the cities, especially the larger cities. Today their presence seems to be tolerated but they move from area to area to make enforcement of regulations difficult. Late in 1999 a police “sweep” was made to pick up the various groups of people who work the streets of Beirut; the Gypsy children were also picked up in this operation. The parents mistakenly thought their children were being stolen or taken from them. They were later released to their parents along with a warning of arrest for the parents if the children

|

were caught on the streets again. According to those interviewed, “the government had hoped to put these people in training programs, etc., but the idea was ill conceived and failed.”

One newspaper report about a Dom family in the village of Qasr vividly depicts the situation that exists for some of the settled Dom in Lebanon. “The scarcity and expense of health services have had an immediate effect on the family. Four of the children, two boys and two girls, are disabled due, Fawzieh said rather vaguely, to ‘a terrible fever’ during infancy. She said they had not been immunized. The boys, both of whom are unable to walk, have been in a hospital in Beirut for the last couple of years. The girls, Fatimeh, 14, and Samaher, 6, are both deaf. Abbas and Adnan, ten and nine respectively, are proud to be the only two of the children ever to have had any schooling. Both in first grade, they wrote their names on a piece of paper as the whole family looked on. They will remain in school until the generosity of a local benefactress wears out, said Fawzieh. And if they have to stop going to school? ‘They’ll have to work as labourers like I have,’ Mohammed said with regret.”/2/

Attitudes toward the Dom in the Lebanese society at large are negative./3/ As in other countries in the Middle East, the Dom are called “Nawar” by the Lebanese. Arab people often use this term in jest with one another, but when used in reference to the Dom it is a strong expression of contempt revealing a deep seeded bias against this group of people. The poorest Lebanese feels that he is superior to the Dom. One individual said, “to be born a Gypsy is to be born under a curse.” Not only do poor Lebanese distinguish themselves from the Dom, but the Dom also make distinctions between the various Dom families. Unacceptable work ethics, cleanliness, and adherence to Gypsy traditions are a part of the criteria of association between the families.

Not all of the Dom are destitute. Some of the men make a single stringed musical instrument called a Rababa. The instrument is not unique to the Dom culture, but is one of the primary products these Gypsy merchants offer. They also make a heavy, wooden container that is used to crush coffee beans. The manipulation of the wooden rod as the beans are crushed makes a musical sound and is used much like a drum. One woman danced for us while the men played the instruments and the grandmother “sang.” Some of the men have turned this craft into a profitable business. They make and sell these items in the markets of almost all the towns in the Bekaa Valley. Some of them travel as far as Saudi Arabia for business purposes.

Until recently the Dom of Lebanon were a nomadic people. The children were educated by means of story telling and watching the adults do the daily tasks of life. Learning by example was the most obvious method and practical means of preparation for life-particularly a life that a Gypsy could expect to attain. Today this attitude prevails in the shantytowns. Children are not encouraged to go to school. The benefits of formal education are not seen as important for the Gypsy way of life-that is, day-to-day existence. Humanitarian agencies have begun to take interest in the Dom. One organization operates an Arabic literacy training school in one of the shantytowns. This school welcomes students of varying ethnic backgrounds. The program focuses on children 10-13 years of age. The school also provides basic health and childcare training for women. Some of the Dom children and adults are now involved in the program./4/

The Dom in the Bekaa Valley demonstrate a more “enlightened” point of view towards formal education. During a brief visit with one family they proudly pointed out one young boy who was studying French. This family is a part of a community that encourages their children to go to the Arab schools.

The language of the Dom is Domari; however, there are many dialects of this language. The Arabic term for their language is Nawari. A Dom from Syria living in Lebanon said that the difficulty of learning the language stems from the Persian (Farsi) influence. While Persian influence may be observed, Arabic has contributed significantly to the language’s development.

By and large, Domari is perpetuated orally being passed from parents to their children through the natural enculturation process of the family. One Dom living in the Bekaa Valley said that they don’t actively teach their language to the children, but that the children pick up the language naturally. Instead of encouraging them to learn Domari, the parents encourage them to learn Arabic knowing that their interaction with the social order around them mandates knowledge of Arabic.

No books or other published materials are available in Domari; however, some of the Dom said that they use the Arabic script to write (transliterate) their language. No official documents or books have appeared in this way, but it serves the purpose of communication by letter. This means of written communication was reported only among the Dom in the Bekaa Valley. This is probably due to a higher literacy rate among this group as opposed to those in the shantytowns.

The Dom are a religious people. Some of them are Muslims while a few of them adhere to Christianity. They show a high tolerance for others’ opinions about religious matters, thus conflict over religion seldom occurs. One man, however, expressed concern that many Dom give no thought at all to religious matters. Even among those who hold to neither Islamic nor Christian teachings there is a general acknowledgment of the existence of a higher power that finds expression in terms of folk religion, superstition and fortune telling.

Very little information about the Dom of Lebanon is available in print. The people of Lebanon know of them, but few people have come to know them beyond the reputation they have in the streets. While everyone recognizes the multi-cultural dimensions of Lebanon they have failed to appreciate yet another facet of their ethnic and cultural make-up that can be found in the Dom people.